3 inches

mort Cohen collection

3 inches

Collectors of naval insignia are few

compared to collectors of the insignia of

army units.

This 1s not surprising given

the Navv's view of unit mns19n1a: there are

far tewer Navv insignia to collect.

There are some Navv insignia,

however, that surely would attract the attention of devo-

tees of army insignia if the insignia were

better known.

The following describes some of these insignia and the

two organizations they represent.

Unusual us the co lector of insignia whc

has not heard of the Office of Strategic Ser.

Vices

• (OSS).

Indeed, so sought after are

OSS_related artifacts and so potent the

OSS cachet, that one can log onto eBay on

almost any day and find items that are as-

sociated - often inaccuratelv - with OSS

Thus it is odd that the Naval Group, China,

a Navy organization whose operations par*

alleled those of OSs. is todav as obscure

as OSS is well known

In 1942 Cmdr. Milton. E. Miles, an of-

ficer with extensive Chia service. was or-

dered by Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of Na-

val Operations, to report to the American

ambassador in Chungking, and there as-

sume the position of naval observer.

9 In written orders. King also imparted to

Miles a set or verbal, secret ordere

Miles was to establish a weather

reporting network: to learn evervthing he

could about the situation in China: to pre-

nare the China

coast for projected amphibi-

ous landings 3-4 ears hence: and. in gen-

eral, to do everything possible to harass

the Japanese in China.

To accomplish his mission,, Milesports. During this time, he picked up basic

Cantonese, Fujianese, and Mandarin lan-

guage skills and learned to appreciate Chi

nese culture. He admired the Chinese. De-

parting the Asiatic for other duty in 1927,

he returned in 1936 aboard the Blackhawk

and then in command of the John D.

Edwards, returning to the states in1939.

Leisurely travel orders allowed Miles,

his

wife and three sons to depart by land over

the still under-construction Burma Road.

"I

had no notion at the time but 2-1/2 years

later the fact that I had served so long in

China and made the trip over the Burma

Road was to lead me back to that ancient

land under very different conditions.

9 In

1939, Miles wrote a paper advocating a US

Navy presence in China as means to obtain

intelligence on the Japanese, especially their

technologies.An underlying American priority as the

US entered WWII in the Pacific was the driv-

ing, gripping, insatiable need for intelligence

on the Japanese and an arguably more im-

portant need for current weather informa-

tion for the fleet at war in the Pacific. Most

weather affecting the fleet came from China,

but as the war started the farthest west the

US had a weather station was Hawaii.

In early 1942, Rear Admiral Willis "Doc"

Lee became King's chief of staff. He had

read Commander Milton Miles' paper ad-vocating a US Navy presence in China. Once

Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Lee told Cdr.

Miles to plan the operation he had recom-

mended, because of his faith in Miles'

knowledge of China,

"but more importantly

his ability to innovate, to initiate, to select

the right men, and then to inspire them to

do the impossible."

The plan set forth three goals: 1. Moni-

tor weather in China as a predictor of Pa-

cific Ocean weather; 2. Recruit coast watch-

ers to monitor Japanese shipping traffic in

and out of coastal China; and 3. Prepare for

a possible US invasion of China to defeat

the Japanese who were occupying it which

in turn would enable the US to attack Japan

from China. King also secretly ordered Miles

to learn everything he could about the situ-

ation in China, and in the meantime do what-

ever he could to help the Navy and heckle

the Japanese.

This direct tasking from King, and the

fact that Miles was to report directly to him

under the cover of working as a military

attaché or US Naval Observer to China, at-

tached to the US embassy, gave Miles sig-

nificant clout.

Miles's mission was to direct the major

US Navy covert effort in Asia and work with

General Dai Li (1897-1946), head of the Chi-

nese Army's intelligence service, the Na-

tonal Bureau of Investigations and Statis-

tics (NBIS). Commonly known as Juntong,

it is said to have comprised between 75,000

to 300,000 agents. Dai, who in 1928 helped

develop China's intelligence organization asdevelop China's intelligence organization as

Chief of the Kuomintang (KMT) Army se-

cret service, had been tasked by Generalis-

simo Chiang Kai-shek to work with the

Americans on what initially was called the

"Friendship Project", a cover for Miles' ac-

tivities.

The genuine respect and cooperation

between the two men made theirs one of

the most effective joint Sino-American mili

tary organizations during the war. Arleigh

Burke explained: "the success of this

strange alignment was primarily due to the

patient building up of mutual understand.

ing and trust which extended down to the

subordinates of each nation. Mutual confi-

dence was created and maintained against

great odds when lack of facilities and

matériel made promises hard to keep."

After Miles's arrival in the Chinese Na-

tionalist capital of Chungking in May 1942,Dai and Miles inspected the Chinese coast

opposite Formosa. While taking cover to-

gether from a Japanese air raid outside the

village of Pucheng, Dai asked Miles to train

and arm 50,000 of his guerrillas in exchange

for allowing US naval activities in China with

his support. Understanding that the guer-

rillas would protect the weather stations and

other US Navy operations, Miles agreed.

The agreement established the need for a

US Navy component as it became the mili-

tary means of organizing and managing the

men assigned to conduct training and any

other activities required of them. This

evolved into a written agreement between

the US and China signed in April 1943 form-

ing the Sino-American Special Technical

Cooperative Organization (SACO), pro-

nounced "socko". As constituted, SACO

was jointly led by Dai and Miles.sending regular weather reports to the US

fleet from multiple occupied areas in the Far

East. The Americans were flown into China

from Calcutta, India. In 1943 SACO had set

up weather, communications and intelli-

gence stations all the way from the border

of Vietnam to the northern Gobi Desert.

Much of the activity was behind enemy lines

along the Chinese coast and China assigned

many undercover forces to protect the

Americans, who often disguised themselves

as coolies. With the help of the undercover

Chinese forces they were generally able to

transit enemy lines undisturbed. SACO per-

sonnel also participated in the surveys of

the China coast in preparation for a pos-

sible landing of the Pacific Fleet. Navy per-

sonnel who had been beach masters in

North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy

came to China to scout the beaches for pos-

sible landing sites.

In his book Miles states that the Chi-

nese guerillas, with SACO equipment and

training, and oftentimes led by US Navy and

Marine Corps personnel, killed 23,540 Japa-

nese, wounded 9,166, and captured 291.

Another account states 71,000 Japanese

were killed as the result of actions by, and

information from, SACO. They destroyed

209 bridges, 84 locomotives, 141 ships, and

97 depots and warehouses, and success-

fully rescued 76 downed aviators. By 1945,

SACO's strength was 2,964 Navy, Army and

Marines with 97,000 organized Chinese guer-

rillas and perhaps 20,000 "loners"

such as

pirates and saboteurs.At the war's beginning the intelligence

Claire E. Chennault's Fourteenth Air Force

received was inadequate. "Stilwell exhibited

a striking lack of interest in the intelligence

problems of the China sector of his com-

mand", Chennault wrote in his memoir. By

Chennault's account, Stilwell was entirely

satisfied with the intelligence the Chinese

provided, although it was outdated, inac-

curate, and useless to the bombers

Chennault commanded. But, worse than his

lack of interest,

"Stilwell specifically pro-

hibited the Fourteenth from any attempts

to gather intelligence. Since the Fourteenth

Air Force was the

only American combat

organization in China and needed fresh and

accurate intelligence... I was again faced

with the choice of obeying Stilwell's orders

literally……or finding some other method of

getting the information so essential to our

operations."The intelligence Chennault had to de-

pend on came from the Chinese War Minis-

try via Stilwell' headquarters in Chungking.

By the time it reached the Fourteenth, the

information was "third hand.…. generally

three to six weeks old,"

and useless for tar-

geting the bombers. Another Chinese intel-

ligence source that Chennault had rejected

was the Chinese Secret Service, because its

notorious KMT secret police was engaged

in a ruthless manhunt for Communists which

would prohibit Chennault's intelligence and

rescue relations with Communist armies in

the field.

Cooperation between Miles

and

Chennault's air force began October 1942

with the establishment of a liaison groupthat eventually became known as the 14th

Naval Unit. This liaison group of SACO pro-

vided weather reports and intelligence on

Japanese targets through radio interception,

photograph interpretation, and field reports.

The Shipping Center of the 14th Naval Unit

gathered information on the routes, car-

goes, and sailing dates of Japanese ships

for the Fourteenth Air Force to bomb. The

unit's homemade radio direction-finders also

uncovered Japanese-recruited agents who

were reporting the flight paths of Fourteenth

Air Force planes from Kunming, and it co-

ordinated efforts with Chinese guerrillas to

rescue downed aircrew.Early in 1943 two SACO naval officers

were detailed to the Fourteenth Air Force

staff working under Chennault's command

to perform photo-interpretation work. The

officers maintained contact with the Pacific

Fleet and provided shipping intelligence

and photo interpretation.

"This effective li

aison paid enormous dividends in attacks

on enemy shipping." In return, the Four-

teeth seeded harbors and waters along the

coast of Japanese-occupied China and

northern Indochina with Navy mines flown

in over the Hump from India. Chennault's

planning staff in Kunming derived their in-

formation about merchant shipping from the

use of aerial reconnaissance, from SACO

coast watchers, and from the intercept and

direction-finding teams of Fleet Radio Unit,

China, at Kunming. Proximity to Chennault's

headquarters (and the close relationship that

grew between the Fourteenth's A-2 and the

Navy) created an ideal situation.

Chennault shrewdly demanded that in-

telligence support from external organiza-

tions be more than purely transactional. Per-sonnel sent by the Navy, and later OSS, to

support Chennault necessarily became a

part of Fourteenth Air Force and worked

under the direction of Lt. Col. Jesse C. Wil-

liams, an oilman with the Texas Oil Com-

pany before the war, who became

Chennault's Assistant Chief of Staff and A-

2 (intelligence chief) in the beginning of

1943. In his memoirs, Chennault evaluated

Williams as one of the few staff officers he

respected.

Chennault's position for the

majority of the war as the primary American

fighting unit in China enabled him to build

Fourteenth Air Force into the intelligence

network he envisioned.

What was soon called the "14th Naval

Unit" grew steadily

- twenty men the first

year and ninety-eight the second

doing

jobs that included photo-intelligence (in

conjunction with the Army's 18th Photo-

Interpretation Unit); planning the delivery

of and charting minefields; providing radio

intelligence, air combat intelligence, and air

technical intelligence;

and rescuing

downed or imprisoned flyers. The last-men-

tioned operation was done with the Chinese

under the auspices of the Navy SACO

teams.

Some of the information that Miles's

people developed from this working ar-

rangement, they passed to Navy agencies

to support submarine attacks on Japanese

shipping and the battles incident to the Al.

lied campaign in the Philippines. In Octo-

ber 1943, a Navy-AAF mining raid (Miles's

mine experts were aboard the bombers)

closed Haiphong harbor by sinking a flee-

ing ship in the entrance channel. The har-

bor remained at least partially closed for the

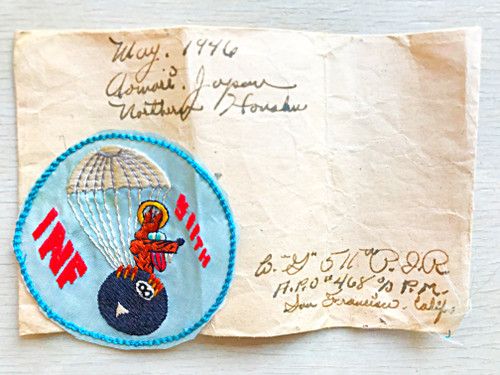

remainder of the war.So much data was coming in about

Japanese ships that alert young officers pre-

pared regular summaries that might prove

useful for war planners. In describing this

activity, Miles provided the symbolism of

the 14TH Naval Unit's unique insigne:

"Called Shipping News ... we sent out

mimeographed copies under a snappy cover

that bore the Naval Unit's new insignia

which combined Chennault' Flying Tiger

with a twelve-pointed Chinese star and the

Navy's fouled anchor. The design was the

same as the one used by SACO Headquar-

ters except this one used the Flying Tiger

instead of SACO's 'What-the-Hell?' pen-

nant. We were never actually given permis-

sion to wear a shoulder patch, but the

SeaBees had one and Captain Jeff Metzel

finally wrote that official permission seemed

hard to get, so why didn't we just go ahead

and wear this one of ours?"

How Miles and Chennault each viewed

the dynamics of the personnel exchange

was likely the key to the program's success.

In his memoirs, Miles described the 14TH

Naval Unit as a part of SACO and Naval

Group China, working within Fourteenth Air

Force to send the intelligence collected by

Fourteenth Air Force to support US Navy

operations. Chennault wrote of the same

personnel in his memoir briefly as "a sizable

group of Miles' Navy officers who oper-

ated in Fourteenth Air Force headquarters

under my command."On 24 April 1944 Admiral King issued

an order creating Naval Group China redes-

ignating all members of the Navy in SACO

as members of NGC and its chief would be

promoted Commodore M. E. Miles. Thus,

the US portion of SACO, which Miles com-

manded, came to be known as Naval Group

China (NGC). NGC would be synonymous

with SACO among those involved.

It was

the umbrella organization for units that per-

formed weather forecasting, advised and

trained Chinese guerillas, and intercepted

and analyzed Japanese radio traffic. Most

of the sailors belonging to SACO were

Seabees but many came from the Navy's

Scouts and Raiders (predecessors of the

Navy SEALs and Underwater Demolition

Teams) because of their experience in co-

vert operations.

Miles, with some of his men, was iso-

lated by the enemy when news of the Japa-

nese surrender reached them five days af-

ter the war was over. A companion article in

a future issue of The Trading Post will fo-

cus more in depth on Naval Group China

and SACO.In 1934, while executive officer of the

Wickes (DD-75), Lt. Milton Miles created a

pennant he referred to as the

"What-the-

Hell Pennant'.

1222111**

Collection of Vice Admiral Milton E. Miles,

US. Navy Historical Center

"We often found ourselves

"snapping

the whip' when, in maneuvering, ships

the whip'

ahead of us did not precisely follow the or-

ders. It was primarily with this in mind that I

asked my wife, one evening, how would you

say

"What the Hell?' on a pennant.

"Well,'

she replied,

*When editors are up against

the problem of suggesting something they"We often found ourselves

"snapping

the whip

when, in maneuvering, ships

ahead of us did not precisely follow the or-

ders. It was primarily with this in mind that I

asked my wife, one evening, how would you

say

"What the Hell?' on a pennant. 'Well,'

she replied,

*When editors are up against

the problem of suggesting something they

are too moral to print, they fill in with ques-

tion marks, exclamation points, and aster-

isks.' So the very next day I had a special

pennant made up

white, with red mark-

ings, arranged as follows: ???!!!***,

For several years I used that pennant

occasionally for monkeyshines [light-

hearted situations]. In fact, I had our sig-

nalman use it enough to acquaint our whole

division with it. But then, in 1939, when I

was on duty in the Far East again, it served

a purpose that had serious attributes de-

spite its nonsense.

In 1939 Miles was skipper of the de-

stroyer John D. Edwards (DD-216) when

he was ordered to Hainan Island, off the

coast of China, where the Japanese Navy

was threatening a coastal village, including

American missionaries. When Miles arrived

at Hainan, he saw several large Japanese

naval ships bombarding the village. The

Japanese flagship hoisted a flag warning

the American destroyer to leave, which put

Miles in a quandary, since his orders were

to protect the American missionaries in the

village.

After considering the situation,caution and backed the Japanese fleet away

from the village. Miles went ashore that

afternoon, gathered up the missionaries, and

departed the following morning. The Japa-

nese Navy, meanwhile, sat offshore, still

wondering about the meaning of the curi.

ous pennant.

"Fortunately, we had given them

enough time before we anchored to make

out our signal and to search for in their sig-

nal books, but not enough time to make sure

that the strange new pennant we were fly-

ing wasn't there. As a result, along came a

young Japanese lieutenant, hurrying toward

us in a pulling boat.

*You cannot anchor

here,' he shouted. .. As skipper of the vis-

iting American destroyer it was up to me to

pay an official call on the Japanese flag-

ship, and I did so as smartly as my men and

I knew how. Still, I wasted little time as pos-

sible in talking with the officer of the deck

and was almost ready to say goodbye when

the admiral himself appeared.

*By the way, Captain', he said in very

good English when he greeted me,

"what

was the meaning of the pennant you flew

as you enter the harbor yesterday?'

"What

pennant was that, Admiral', I asked as in-

nocently as I could, though I edged toward

the accommodation ladder at the same time.

*Why, this pennant,' he replied, breaking

out a very glossy print showing the John

D. Edwards coming out of the haze and

plainly flying both the red and white stripedinternational code pennant and the What

the Hell pennant with its question marks,

exclamation points, and asterisks.

"Oh°

then, I nodded.

*Well, Admiral, it could be

that the Japanese Navy is so busy these

days that the boys haven't had time to keep

their signal books up-to-date. Good day, sir.

And, having saluted him and also the Japa-

nese colors on the cruiser's turn, over the

side I went."

In August 1939, after Miles had been

transferred to Washington, a Japanese in-

quiry had been passed down together with

the print of the picture the admiral had

shown him, with an accompanying memo

that asked: "What is the meaning of this

pennant you flew on the John D. Edwards?"

But now that the war had come and mem-

bers of the Navy Group China were looking

about for an acceptable bit of insignia, the

what's the hell pennant seemed made to

order for our purpose.

99

Throughout World War II, Milton

Miles' "What-the-Hell?"

pennant was the

unofficial emblem of SACO and was often

found flying at SACO camps throughout

China. It was also incorporated into a num-

ber of the SACO and Naval Group China

insignia as will be seen in the next install-